This short-scale film analysis has been written by Almira Tabaeva in the framework of a feminist research maqaal collectiv, sponsored by the British Council’s Creative Collaborations programme.

*Temir xotin, or Iron Woman is a 1990 film directed by Isamat Ergashev, based on Sharaf Bashbekov’s work of the same name.

Cinema, often seen as a mirror to society, not only reflects reality, but also actively shapes it. Through its visual stories and characters, films have the power of influencing cultural norms and the ways of how people view themselves and others. In Uzbekistan, cinema has been a compelling agency in constructing gender discourse, particularly in the portrayal of women. Since gaining independence in 1991, the country’s film industry has encountered remarkable transformations, striving to delink from its previous Soviet cinematic past and reaffirming Uzbek national identity in current cinematography. The concept of national identity is often tied to the ongoing reinterpretation of cultural heritage and societal values shaped by socio-political agendas. Cinematic portrayals of women, central to these narratives, often reinforce patriarchal norms, putting aside diverse perspectives, particularly those of women.

Drawing on an analysis of Uzbekistani movies produced after 2000, Almira Tabaeva examined how cinematic narratives construct and contest women’s roles within the tensions of tradition and modernity. Critiquing the male gaze that persists in framing women as traditional archetypes in relation to societal expectations through cinematography, author also emphasised the potential of cinematic storytelling to challenge these narratives and reimagine women’s agency in contemporary Uzbekistan.

Glimpse of the Past – the Legacy of Soviet Influence in Women’s Image in Cinema

Women’s representation in Uzbekistani cinema has historically been deeply rooted in the country’s rich and complex historical culture. Women have always been depicted as the pillars of family life embodying values of dutiful daughter, mother, obedience and sacrifice. These representations showcase local socio-cultural norms that continue to shape the expectations of women’s roles both within the household and the broader community.

However, these portrayals cannot be fully understood without acknowledging the historical impact of Soviet colonisation in Central Asia. During the Soviet era, campaigns like Khujum (unveiling) sought to “liberate” women from “backward” lifestyles, encouraging their entry into public spaces and promoting gender equality through state-mandated policies. Films such as Her Right (Turning Point) directed by Grigoriy Chernyak (1931) exemplify this propaganda, portraying Tadji, a young Uzbek woman, leaving her husband and village to become a model worker at a factory. While celebrating her emancipation, the film reflects the Soviet ideological framework, where gender reforms were depicted as successes of communist values. Nevertheless, these efforts often clashed with embedded cultural norms, leading to resistance and a complex negotiation of women’s identity caught between tradition and Soviet modernity.

Furthermore, the Soviet emphasis on women’s public roles also glorified motherhood as a contribution to the state, with women bearing numerous children being awarded titles like “heroine mother.” This legacy influenced societal attitudes toward women, intertwining notions of motherhood with both tradition and political ideology. While women like Tadji were idealised as agents of change, this narrative overlooked the real challenges women faced, and the ways these women asserted their agency outside Soviet frameworks. Despite these pressures, women maintained cultural resilience, negotiating their roles within the constraints of Soviet modernity.

For example, the film Temir Xotin —Iron Woman (1990), based on the play by Sharof Boshbekov, provides a stark reflection on these dynamics, albeit from a late-Soviet perspective. The story follows Qo‘chqorvoy, a chaotic and irresponsible man whose wife leaves him. His inventor nephew creates a female robot, Alomatxon, as a stand-in wife for Qo‘chqorvoy. Alomatxon tirelessly performs domestic and agricultural duties, embodying the idealised woman living Uzbekistan. However, her eventual burnout underscores the unsustainable demands placed on women in real life. Through Iron woman’s “death,” who couldn’t bear all the domestic chores, the film poignantly reveals the dehumanising expectations of women’s labour and the patriarchal structures that perpetuate them. In the end Qo‘chqorvoy realizes that “Axir u bitta o‘zbek ayoli qiladigan ishning yarmini qildi, xolos-ku!” (After all, she “Iron Woman” only did half of what an Uzbek woman normally does!). Iron Woman challenges the idealisation of Soviet reforms by highlighting how these policies often left women in a liminal space, where they were expected to embrace public roles without abandoning their traditional duties.

After independence, the film industry sought to reclaim its cultural narrative, exploring themes of identity, tradition, and modernity through a distinctly local lens. This transition from Soviet to post-independence cinema not only reshaped the thematic focus of Uzbek films, but also set the stage for substantial growth in production. For example, in 2016, only 7 films were produced in Uzbekistan. However, by 2020, this figure had increased to 30 films per year, as noted by Firdaus Abdukhalikov, General Director of the Cinematography Agency of the Republic of Uzbekistan. Later, Uzbekistan’s film industry has experienced significant growth. In 2023, the Uzbekistan Cinematography Agency reported the creation of 113 film projects, marking a nearly 300% increase in production volume compared to 2017. But, while the film industry blossoms, concerns over the quality of content amid this rapid expansion remain pressing.

Contemporary «Temir Xotin»: The Cinematic Evolution of Uzbekistani Women

The film production in Uzbekistan remains connected to the political landscape reflecting and reinforcing state agendas. The likelihood of the films being screened on television or in cinemas also depends on its alignment with state-approved narratives. This connection shapes the themes that filmmakers choose to explore, and also the genres that are prioritised. The focus on moralistic genres reflecting Uzbek national identity – a set of ingrained cultural and traditional values, is an implicit form of censorship, where certain topics, such as authority, gender hierarchies, or societal taboos get sidelined. For this short-scale analysis, I have focused on films produced in the last two decades with a focus on the most iconic and widely recognised film productions. These movies not only gained local acclaim, but also resonated with broader audiences across Central Asia. These narratives reflect the complexities of women’s lives in a family and wider society.

From 2000’s and onward, women’s representations predominantly fit into “kelin” “mother” and “wonder women” categories, shaped by prevailing norms and stereotypes. While women are expected to be educated and well-mannered, these films often reinforce the notion that women must first conform to the traditional roles before pursuing education and autonomy, or they risk facing societal rejection. At the same time, cinematography reflects ongoing discussions about women’s rights, access to education, and their roles in public life. underscoring the tensions between tradition and modern aspirations.

In recent years, there has been a shift to depict these traditional archetypes of women, where the concept of kelinhood (bridehood) and motherhood played a significant role. The kelin is expected to adhere to family duties, with her identity closely tied to marriage, domestic labour, and her relationship with her in-laws. Such narratives reinforced the ideas that a woman’s worth is primarily determined by her ability to navigate these roles. Alongside kelinhood, the notion of motherhood holds significant importance, yet places a heavy burden on women. Even today, women navigate both traditional and modern roles, where the recognition of their broader potential remains contingent upon their ability to fulfil longstanding ideals of motherhood.

The notions of Kelinhood and Motherhood in cinema

The concept of kelinhood has always been a prominent motif in films made in Uzbekitan, illustrating the expectations placed upon women within the context of marriage. One of the most well-known contemporary films that shows a rich narrative about gender roles is “Super Kelinchak” (2008), meaning “Super Daughter-in-law”, directed by Bakhrom Yoqubov. The film gained popularity not only in Uzbekistan, but also across other Central Asian countries. As a result, even today, a woman who successfully balances the submissive kelin role in her husband’s extended family, while also excelling in her career, is referred to as a “Super kelinchak”.

The story in the film revolves around Diana, a non-Uzbek woman, who marries into a traditional Uzbek family. She is subjected to constant scrutiny from her mother-in-law, who represents the intergenerational transmission of patriarchal values. On the other side, Diana is also seen as an independent and non-conformist woman. She embraces all her kelin duties turning them into acts of perseverance, and gradually transforming her relationship with her in-laws. Her resilience signals that patriarchal power should be subverted from within the household itself. The different scenes, such as, when Diana’s husband said: “I’ll make her sweep my yard”, while planning to marry her, and Diana repeatedly saying “Kechiring” (forgive me) as she does morning chores and sweeps, highlight how domestic labour is used to reinforce power dynamics within family. This dynamic is a hint to a tenuous critique of societal roles imposed on women, with Diana having have to prove that endurance and resilience can coexist with a traditional kelin role.

Thus, the ultimate message of the film was: while modernity may clash with tradition, they are not irreconcilable. This portrayal reflects broader societal expectations for women in Uzbekistan, where adherence to traditional values remains paramount. There are currently over 20 films with titles that include the word “kelin” often perpetuating reductive portrayals.

This analysis of women’s cinematic representation aligns with Turaeva’s (2020) study, in which she applies the concept of “liminality” to understand the transitional status of kelins. Turaeva (2020) noted that kelins face challenges in their early years after marriage gradually turning into respected kelins through their hard work, resilience and obedience. Consequently, I argue that such societal structures, which limit women’s agency remain largely unchallenged in cinematography, and in real life. Women in such narratives are praised for their endurance within traditional frameworks. However, the film industry stops short of questioning whether these frameworks themselves NEED to evolve.

Motherhood, like kelinhood, is another recurring theme in contemporary Uzbekistan’s cinema and reflects the deep-rooted cultural importance of family. Mothers are often represented as protectors of tradition, and motherhood is seen as a duty rather than a choiceю For instance, in Ona (2007) («Mother»), the film focuses on the cultural reverence for motherhood, depicting mothers as family’s moral backbone, and embodying self-sacrifice and strength despite personal hardships.

The central mother figure in Ona, despite her own heart disease, continues to support her family, reinforcing the ideal of the devoted mother. In contrast, the kelin in the film is portrayed in a negative way, pretending to be ill to avoid housework and hindering traditional expectations of dutiful hizmat (service) and respect toward elders. This conflict between the selfless mother and the selfish kelin leads to the tragic death of the mother, highlighting the cultural tension between kelinhood and the family structure.

The film critiques the kelin’s failure to conform to her traditional role, indicating that any deviation from these expectations can lead to family discord. This portrayal underpins the rigid societal expectations placed on women in society, where motherhood is glorified and kelins are expected to navigate complex family dynamics with obedience and hard work. The film serves as a cautionary tale about the importance of adhering to traditional values within the family, illustrating the consequences of failing to uphold these roles.

Likewise, in The Stubborn Daughter-in-law (O’jar Kelin, 2012), the focus is again placed on young women, particularly regarding women’s ability to bear children. The main character’s failure to bear a child contradicts the traditional role of a mother, thus becoming a focal point for criticism from all sides. Her mother-in-law, husband’s colleagues, relatives, call her “lifeless tree”. Even her own father calls her “a barren daughter”. The film explicitly accentuates the intense social stigma surrounding infertility in Uzbekistani society, where a woman’s worth is predominantly tied to her ability to reproduce.

A similar theme is screened in O Maryam, Maryam (2012) by Bahrom Yoqubov. The heroine, Maryam, while deeply loves her husband, cannot bear a child, which further becomes a devastating obstacle in their relationship. Her husband, Erkin faces social expectations and judgement and turns to alcohol. Maryam feeling guilty over her infertility suggests her close friend marry her husband in order to make him happy, at the same time she refuses to leave him unable to imagine her life without Erkin. This is a pure illustration of the pressure placed on women to bear children and how infertility becomes a societal judgement that women internalise. Maryam’s actions highlight how societal norms can distort women’s autonomy and self-worth.

What is missing? Struggles of Female Filmmakers

A critical gap in Uzbek cinema lies in the absence or the underrepresentation of female filmmakers and their perspectives, which could challenge and diversify the narrative landscape. Laura Mulvey, a feminist film theorist and filmmaker discussed the role of women in films and argued that women are often portrayed as “objects” because of the lack of diversity in directors. Since men were mainly in control of the camera, the audience experiences the film from a male perspective.

What is a Male Gaze?

Introduction to Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”

Laura Mulvey introduced the concept male gaze in her essay ”Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), in which she examines how women are depicted in cinema to satisfy patriarchal desires. She asserts that films often objectify women by framing their identity primarily in relation to male characters. This perspective operates through three key dimensions: a) camera’s perspective – framing and depicting scenes, often shaped by male directors or cinematographers; b) audience’s perspective – how viewers are positioned to adopt the gaze of the camera, experiencing the narrative through its lens; and finally c) characters’ perspective – how characters of the film gather and share information, often privileging a male point of view. This framework is not only a critique of commercial cinema but also is applied broadly to literature, art, and media that sustain patriarchal narratives.

Male Gaze in Uzbekistani Cinema

Relating male gaze to our context, recently, Binazir Yusupova, a feminist scholar, insightfully critiqued the representation of women in online choyxona spaces within Uzbekistani media. She argued that women’s rights in media still remain predominantly influenced by male gaze, where women are depicted from male perspectives. She also noted that feminism is predominantly being studied through a historical approach in the region. Thus, building on Mulvey’s theory of the male gaze and building on Yusupova’s critique of women’s representation in media with male gaze, I contend that Uzbekistani cinema perpetuates these patriarchal perspectives. The films analysed films (based on those I watched, though many others exist) frame women’s narratives through traditional archetypes, restricting their agency and often defining them in relation to male counterparts or societal expectations.

Analysing the films with this lens, one can see that the male gaze in Uzbekistani cinema is widely reflected in how women are often confined to traditional roles such as the kelin or mother. For instance, films such as Super Kelinchak and Stubborn Kelin reinforce the notion of the ideal daughter-in-law by celebrating her conformity to traditional expectations. Films like Super Kelinchak, Ona and O Maryam, Maryam, reinforce these archetypes, limiting the portrayal of women’s autonomy and agency.

In countering this male gaze Mira Nair, an Indian filmmaker, has become famous for her ability to weave personal and cultural stories into globally resonant narratives. Nair’s films, such as Monsoon Wedding and Salaam Bombay!, highlight the intersection of individual struggles with broader societal issues, offering a lens through which local stories acquire universal meaning. But, we don’t have to go that far, we also have our “Woman with a camera”, a female filmmaker Umida Akhmedova.

Though Umida Akhmedova’s genre is different from mainstream Uzbekistani cinematic narratives, her work opens a way to critical space in contemporary gender discourse around women’s representation. Her approach, grounded in documentary realism and critical examination aligns with the insights of visual anthropology, a field that studies how visual culture -films can shape and reflect cultural norms.

source: Voices on Central Asia

Akhmedova’s critical lens aligns with Laura Mulvey’s concept of the male gaze, as her work not only resists such objectification but also actively disrupts the traditional narratives that reinforce these roles. Her films and photobooks offer a counter-narrative that centres women as subjects of their own stories rather than passive symbols within a male-dominated discourse. However, she has faced challenges in her personal and creative journey, marked by public censure, a lawsuit, due to her critical stance on societal norms. Her work is an example of what difficulties women face in achieving self-realisation in the film industry within a patriarchal society. Akhmedova has been charged for her works: the photobook ”Women and Men: From Sunrise to Sunset” (2007), which captures everyday scenes of life in Uzbekistan, and the film ”The Burden of Virginity” (2008), a fictional account exploring the controversial practice of “virginity checks” (Art Asia Pacific, 2023). Her works sparked controversy, highlighting the risks women creators face when challenging cultural taboos and questioning traditional values in a patriarchal context. Akhmedova’s case is a clear reminder of the limitations placed on women’s expression, and the price they have to pay for pushing the boundaries of societal expectations.

Another example is Saodat Ismailova, an artist and filmmaker from Uzbekistan, known for her artistic work, such as blending film, performance and traditional materials to explore themes of memory, resilience, and spirituality. She founded the research group Davra to promote Central Asian culture and continues to contribute to international exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale and documenta fifteen. Ismailova’s documentary “Zukhra” (2013) depicts a collective memory of women in Uzbekistan through the symbolic depiction of a young woman lying on a bed, seemingly on her deathbed or in a state of deep lethargy. The sleeping woman becomes a metaphor for the silent endurance of women. The background sound plays a crucial role in the narrative with sounds of people, wind, water, Soviet agitprop, old and contemporary songs. This natural imagery creates a connection between the woman’s experience and broader historical narratives through the cyclical nature of life and memory. Zukhra (2013), functioning outside the commercial mainstream, powerfully portrays women’s experiences through a symbolic narrative. Ismailova’s works exemplify how women filmmakers behind the camera can challenge the limitations of male gaze and reclaim space for women’s identities and histories.

Yet, despite the existence of such talented female filmmakers, their works often remain inaccessible to the larger population, where they are most needed. This lack of visibility is a remarkable gap in the Uzbek Film industry, where the absence of women behind the camera limits various perspectives. Women filmmakers could bring insider perspectives on women’s lives and representations through their own lived experiences. Without their voices in key creative roles, the male gaze continues to reinforce existing stereotypes and fails to capture the real picture. Without the voice of women in key creative roles, the potential for deeper exploration of women’s autonomy, agency, and the tensions between tradition and modernity remains underdeveloped. The recent women’s film festival was therefore crucial, as it provided a platform for female filmmakers to reclaim their narratives and offered diverse portrayals of women’s experiences, bridging this gap.

Janub Shamoli (Wind of the South) film festival by maqaal collective

From August 13 to 18, 2024, maqaal collective organised the inaugural “Janub Shamoli” (Wind of the South) Festival, hosted in the Art Station by Silk Road University in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Sponsored by the British Council’s Creative Collaborations programme, the festival celebrated women’s films from the Global South, showcasing over 20 films directed by women from Central Asia and beyond.

A Magical Substance Flows into Me (Jumana Manna, 2016)

QYZQARAS: Harshness of the Silk Road (Central Asian Filmmakers)

- Grief (Kali Aibota, 2023)

- The Late Wind (Shugyla Serzhan, 2023)

- Aqtalğan / Невиновен (Karina Enteri, Aruzhan Serikbayeva, 2023)

- Kündelık.Dubai (Aiganym Mukhamejan, 2024)

- mockumentary (Sana Serkebaeva, 2024)

- I am not where you think I am. I am where you think I am not (Salt Salome, 2024)

- FREE:AYOL (Dariya Kanti, 2023)

- Project Mayhem: Dolphin House II (Tomiris Batalova, 2022)

Women Make Docs: I Have Nothing to Lose (Central Asian Filmmakers)

- Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Side Chicks (Intizor Otaniyozova, 2024)

- In Her Room (Rusudan Khubutiya, 2023)

- I Have Nothing to Lose (Bakhyt Bubikanova, 2018)

- 64 Reasons Why Everything Went Wrong (Dilnaz Abraimova, 2023)

- Jonjuvoz (Masuma Mahamadaliyeva, 2024)

- Izdeu (Nazira Karimi, 2022)

- Се Хоҳаракон (Fariza Giyosidinova, 2024)

- DYAD (Aidan Serik, 2023)

- My Mother’s Wound (Gulzat Matisakova, 2021)

Forgetting Vietnam (Trinh T. Minh-ha, 2015)

DAVRA Collective (Central Asian Filmmakers)

- Her Right (Saodat Ismailova, 2020)

- Alaqan (Aïda Adilbek, 2022)

- Hard to Digest (Nazira Karimi, 2021)

- Autonomy (Zumrad Mirzalieva, 2022)

Ever Since I Knew Myself (Maka Gogaladze, 2024)

A Night of Knowing Nothing (Payal Kapadia, 2021)

Niki Kohandel: Films Screening & Artist Talk

The Sparrow is Free (Niki Kohandel, 2021)

Minevissam (I am writing) (Niki Kohandel, 2023)

Just Another Year (Niki Kohandel, 2020)

…- then love is the name (Niki Kohandel, 2022)

Albalo (Niki Kohandel, 2021)

It is worth mentioning that the genre of these documentary, experiential and fiction films definitely differ from the mainstream TV films. Nevertheless, the festival attempted to counter the male gaze and foreground the female gaze – a cinematic perspective that centres women’s experiences and narratives, challenging the dominance of Western and male-dominated storytelling traditions. From intimate lived experiences and personal resilience to broader commentaries on systemic inequalities and distortions, the films allowed women filmmakers to rewrite their stories.

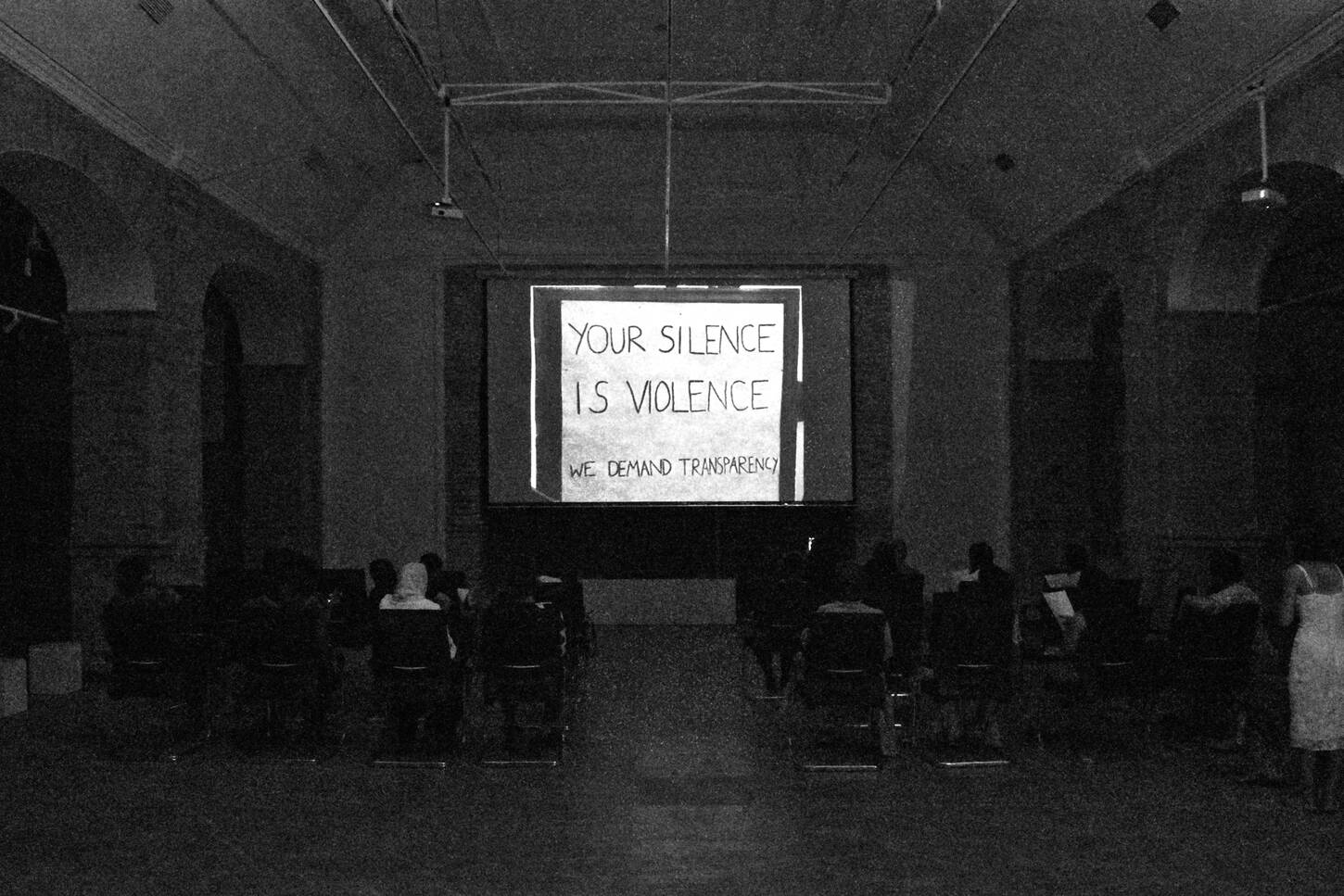

A key feature of the festival was its openness to dialogue and collective reflection. Following each screening, the audience were invited to participate in discussions with filmmakers and researchers, fostering a vibrant exchange of ideas and opportunity to be heard. The festival is an example of the transformative potential of cinema in challenging patriarchal norms and expanding the horizons of representation. By centering women’s narratives by women themselves, particularly from historically underrepresented regions, it marks a significant step towards a more equitable global cinematic landscape, one where the female gaze is not an exception, but a norm. The festival had a message: storytelling is a powerful tool for social change, and the stories of women must no longer remain on the periphery.

This short-scale film analysis has been written in the framework of a feminist research maqaal collective, sponsored by the British Council’s Creative Collaborations programme.

References

Art Asia Pacific. (2023). Preserving the Past: An Interview with Umida Akhmedova. Retrieved from https://artasiapacific.com/people/preserving-the-past-an-interview-with-umida-akhmedova

Chernyak, G. (Director). (1931). Her Right (“Turning Point”) [Film]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gQlq6AuzWWU

MIR24. (2023). Как развивается киноиндустрия в Узбекистане? [How is the film industry developing in Uzbekistan?]. Retrieved from https://mir24.tv/news/16569843/kak-razvivaetsya-kinoindustriya-v-uzbekistane?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6–18.

Turaeva, R. (2020). Kelin in Central Asia. In The Family in Central Asia. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1515/9783112209271-011

UZA. (2023). Uzbekistan’s filmmakers won 15 top international awards in 2023. Retrieved from https://uza.uz/en/posts/uzbekistans-filmmakers-won-15-top-international-awards-in-2023_555546?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Yoqubov, B. (Director). (2008). Super Kelinchak [Film]. (“Super Daughter-in-law”).

Yoqubov, B. (Director). (2012). The Stubborn Daughter-in-law (O’jar Kelin) [Film].

Yoqubov, B. (Director). (2012). O Maryam, Maryam [Film].

Yusupova, B. (2024). Эркаклар онлайн чойхонасини ўтмишда қолдириш вақти келди [It’s time to leave the men’s online tea house in the past]. Retrieved from https://sarpa.media/male-gaze-uz/