EN | RU

sarpa starts publishing materials produced by the independent media Beda in collaboration with the participants of the Suspended matter research group on the environmental consequences of Soviet policy in Eastern Europe, the South Caucasus and Central Asia.

The text of Alisher Khassengaliyev, a participant in the project and its follow-up conference, is an example of integrative writing: it combines academic and activist positions, the personal and the collective, the poetic and the political. The notes about the trip to the Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons to the UN headquarters in New York contains the history of the STOP initiative, of which Alisher is a part, the history of the activist struggle against nuclear colonialism in Soviet and post-Soviet Kazakhstan, deeply personal experiences of the day of the speech at the UN and the search for sources of hope and strength to continue the work.

Prologue

It all began in 2021 when I had the privilege of partaking in the School on Non-proliferation and Nuclear Disarmament in Astana, organized by FES Kazakhstan. The following year, I was honored to help publish the Kazakh edition of Dr. Togzhan Kassenova’s enlightening work, “Atomic Steppe: How Kazakhstan Gave Up the Bomb”. These experiences not only broadened my knowledge but introduced me to five remarkable young Kazakh activists and experts, who have since become cherished friends and kindred spirits.

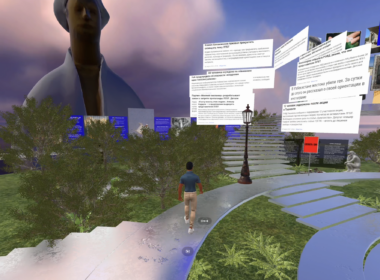

In 2023, driven by our shared aspirations, we each applied for participation in the 2nd Meeting of the States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (2nd MSP TPNW) as representatives of the Youth4TPNW delegation. Much to our collective surprise, all six of us were invited to join this gathering at the UN Headquarters in New York. Thus, our journey together commenced.

With this unexpected turn of events, we founded the Steppe Organization for Peace (STOP): Qazaq Youth Initiative for Nuclear Justice. With a focus on decolonization, transgenerational justice, and feminism, our mission was to amplify the voices of our people within the global discourse on nuclear disarmament. Our collaborative efforts culminated in organizing a side event during the conference, marking a historic milestone for our collective endeavor.

Titled “Kazakhstan’s New Generation and Nuclear Politics”, our side event on November 30, 2023, provided a nuanced exploration of Kazakhstan’s path towards nuclear justice and disarmament.

At the event, Aigerim Seitenova articulated STOP’s vision and mission to an audience of representatives of international organizations, activist initiatives, diplomats, and scholars.

Under the guidance of Medet Suleimen, our panel emphasized Kazakhstan’s pivotal role in nuclear politics. Zhibek Toktash underscored the transformative potential of education in nurturing a generation dedicated to peace and disarmament. My presentation focused on decolonial methodologies and Memory Policy as crucial components of the pursuit of nuclear justice.

Yerdaulet Rakhmatulla highlighted the need for a regional approach to nuclear security and the cultivation of stronger Central Asian solidarity. Adiya Akhmer advocated for feminist and decolonial frameworks in nuclear policy and victim assistance.

In my personal reflections, I delve into my feelings on that momentous day, connecting them to the enduring legacy of Soviet nuclear colonialism. I use the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site as a case study, and the struggle of the Kazakh people against nuclear tyranny.

Personal Reflection. New York, 11/30/2023

It’s a heavy, suffocating New York subway, my friends and I navigate it, our bodies weighted down by jetlag and our responsibilities. We’ve wandered through the city for days, enveloped in a haze, surrounded by towering skyscrapers and a sea of unfamiliar faces. The UN building looms large, adding to our overwhelming emotional burden.

But today is no ordinary day — it is a day we have been tirelessly working towards. Today, we stand on the precipice of our side event, ready to illuminate the struggles of the New Generation of Kazakhstan and our unwavering stance on nuclear politics. We have poured our hearts into this endeavor, striving to share the stories of our people and the resilience of our spirit with the world. Failure is not an option today. Our voices must resonate with clarity and conviction.

As we pass through security and navigate the maze-like corridors of the UN Headquarters, anxiety gnaws at us. Small mishaps, like the incorrect event name on the entrance screen, add to our nerves. Yet, we press forward, entering the auditorium — a modest space charged with anticipation and uncertainty.

As people trickle in, we hurriedly place Kazakhstan chocolates on each seat, our hands trembling with nervous energy. Just when the tension threatens to overwhelm us, Togzhan arrives. Her presence is a balm to our frayed nerves, a reminder of our shared purpose and strength. Embracing her, we feel the ground beneath us steady, anchoring us in the reality of our mission.

That’s it, we take a deep breath, trying to steady our quivering voices as we prepare to deliver our speeches. Jibek sets the stage with her impassioned words on the importance of education in dismantling nuclear threats and fostering peace. She emphasizes that a broader group of people, particularly the emerging leaders of Kazakhstan, must grasp the enduring repercussions of nuclear testing on our land and comprehend the valor of the Nevada-Semey movement’s heroes. Our collective journey toward decolonizing consciousness hinges upon the dissemination of knowledge, the pursuit of understanding. Indeed, we stand as a testament to the transformative power of education. Schools on non-proliferation and nuclear disarmament in 2021 and 2022 have borne fruit in our presence here today, gathered in New York for the second MSP to the TPNW. Togzhan’s groundbreaking book, translated into Kazakh for the first time, illuminates a vital chapter of our history, shedding light on the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site and the courageous souls who safeguarded our right to existence. Jibek’s enthusiastic address serves as a poignant reminder of the journey we must continue to traverse together.

Now it is my turn to speak. My voice wavers, but I press on, determined to shed light on the malicious legacy of Soviet nuclear colonialism. I delve into the history of the Semipalatinsk test site, exposing the environmental and humanitarian injustices wrought upon our land and people. Each word feels like a small act of resistance, reclaiming our narrative from the grip of colonial oppression.

The once-vibrant East-North Kazakh land, rich with life and lore, was exploited by the Soviet regime for nuclear testing. The repercussions were dire — radiation contamination, ecological desolation, and the stifling of Kazakh voices. It serves as a reminder of the enduring echoes of colonialism, resonating across generations.

The Semipalatinsk Test Site (STS), nestled amidst the northeast Kazakh steppe, approximately 150 km west of Semey, bordering the Abay and Pavlodar Regions, spans a desolate 18,500 km², with its tendrils extending over 304,000 km². Between 1949 and 1989, the site witnessed at least 468 nuclear tests, involving 616 devices. The cumulative force of these tests dwarfed the devastation wrought by the Hiroshima atomic bomb, casting radioactive fallout from 125 atmospheric and ground detonations, alongside 169 subterranean tests, leaving a trail of contamination in its wake. These numbers are etched into my memory.

Throughout its operation, Soviet authorities obscured the true toll of nuclear tests, leaving nearby residents ignorant of the looming dangers. Even in the face of catastrophic incidents, authorities offered scant advice, suggesting nothing more than closing windows and seeking shelter indoors. Following the ban on atmospheric testing, subterranean detonations ensued, further polluting the soil and groundwater with grave consequences.

But why can we label the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site as a prime example of nuclear colonialism? Nuclear colonialism entails dominant nations wielding advanced nuclear capabilities to subjugate weaker entities through diplomatic, economic, and strategic coercion, as well as monopolizing nuclear resources and knowledge.

Nuclear Colonialism

Dominion over Kazakhstan: The Soviet Union, as a formidable nuclear power, imposed its authority over Kazakhstan, its constituent republic, by establishing and operating the Semipalatinsk Test Site. Kazakhstan lacked the autonomy to oppose or contest the establishment of such a site within its borders.

Diplomatic and Strategic Coercion: The presence of the STS and the relentless testing therein served as a testament to the Soviet Union’s nuclear might, serving as both a deterrent strategy and a diplomatic tool during the Cold War.

Control over Nuclear Expertise: The Soviet Union tightly controlled the data, research, and knowledge generated at the STS. The true extent of the tests’ impact remained shrouded until the site’s closure when studies began to unveil the scale of devastation.

Exploitation of Indigenous Territories: The selection of the Semipalatinsk region for nuclear experimentation was not incidental. The sprawling steppe was perceived as remote and “uninhabited,” despite being home to Kazakh communities.

Absence of Informed Consent: The local populace was neither consulted nor informed about the nature, purpose, or risks of the tests. Tests often occurred with minimal warning, with nearby villagers sometimes mere kilometers away.

Health and Environmental Ramifications: Extensive nuclear testing exposed the local population to significant radiation, resulting in a surge of cancers, birth defects, and other radiation-induced ailments. The environment suffered considerable damage, with soil, water, and air contamination affecting agriculture, livestock, and wildlife.

Economic Exploitation: Beyond nuclear testing, Kazakhstan served as a crucial source of uranium for the Soviet nuclear program. Mining activities were often conducted with little regard for environmental preservation or the welfare of the local workforce.

Amidst the darkness, a beacon of hope emerged in the form of the Nevada-Semey movement. Fueled by grassroots activism and unwavering resolve, it mobilized our people to fight against nuclear tyranny.

The Nevada-Semey movement, uniting thousands across the nation, established grassroots networks across Kazakhstan, with support from everyone — from intellectuals to workers. Massive demonstrations and local strikes captured global attention, fostering collaboration between Kazakh and American Indigenous anti-nuclear activists. The movement seamlessly melded grassroots mobilization with public diplomacy.

Through a blend of local efforts and international collaboration, the Kazakh people succeeded in shuttering the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site — on August 29, 1991, it ceased operations.

The Nevada-Semey movement not only closed the test site but also highlighted the maturity and unity of Kazakhstan’s society, our commitment to defend our rights and survival. Kazakhstan asserted itself globally. Leveraging public diplomacy, Kazakh activists forged grassroots connections beyond Moscow — linking up with activists, diplomats, journalists, and experts worldwide.

Buoyed by local triumph — the closure of the Semipalatinsk test site — the movement pivoted to advocate for nuclear disarmament. Kazakhstan’s anti-nuclear struggle founded its independent foreign policy, emphasizing principles of non-proliferation and disarmament. Our journey from a nuclear colony to a global leader in anti-nuclear advocacy speaks to the power of collective action and resilience. We refused to be silenced, reclaiming our agency and shaping our own destiny. And as we move forward, guided by principles of justice and intergenerational solidarity, we honor the sacrifices of our ancestors and pave the way for a brighter future.

As I conclude my speech, I find encouragement in the approving nods from my friends and Togzhan. Each of our speeches reflects our shared commitment to justice and memory.

Adiya speaks last. Her words linger in my mind, each one full of pride, resilience, empathy, and courage. Her speech, a poignant testament to transgenerational justice, strikes a chord within me. It illuminates a truth I had previously overlooked: we carry a profound duty to honor our ancestors, to uphold their legacy with dignity and reverence. This realization weighed heavily on me. I had underestimated the significance of our presence at the conference. We were not merely recounting our stories or sharing perspectives; we were entrusted with a sacred mission that transcended our individual narratives.

It became clear that our purpose extended beyond ourselves — to amplify the silenced voices of our forebears, to shed light on the untold history of the Semipalatinsk test site. Our presence was not incidental; it was intentional, imbued with the responsibility to advocate for education, memory preservation, and reform of victim assistance. By embodying our ancestors’ voices, we became conduits for their stories, the narratives long suppressed. This realization was both humbling and empowering, igniting a fervent determination to carry forth their legacy with unwavering dedication and resolve.

As the event concluded and as the applause faded, tears welled up in our eyes. It was a surreal mix of relief, accomplishment, and raw vulnerability. We found solace in each other’s presence, especially Togzhan, who understood our journey intimately.

I’ll never forget her words as we stood by the elevator. She urged us to prioritize our mental well-being, emphasizing the importance of self-care and rest. It was a simple yet profound reminder, resonating deeply with us in that moment of exhaustion and triumph.

In subway, the rhythmic pulse of the train stirs my thoughts, I can’t help but yearn for the expansive embrace of the steppe. My heart aches for its vastness, its endless beauty. I find myself longing to be amidst the very landscape Abai depicted with such eloquence:

“Your soul trusts in the mercy of Allah,

who has breathed life with spring into the earth.

The cattle have grown fat in the steppe, abundance descends,

and human’s spirits soar, he comes from the time of losses.

Everything, except for the black rocks, is warm and pulses with life.

Everyone is so generous that the skinflints are angry.

You follow the rebirth of the world with rapture —

the soul finds its stronghold in the Creator.”

“Spring” by Abai Kunanbaiuly, translated by Dorian Rottenberg

For me, the steppe isn’t just a place; it’s the heartbeat of existence. It’s where we are born, where we return in death. Our nation’s story begins and ends in the steppe, enduring countless trials yet always emerging anew, thanks to its resilience. Despite wars, upheavals, and even nuclear tests, the steppe endures.

How could anyone defile this sacred land with nuclear experiments? How could they dare disturb its natural harmony? Those who sanctioned such actions were lost in their own arrogance, failing to see the deep wisdom inherent in the steppe’s cycles.

Yet despite their ignorance, the steppe and our people persist. We’ve weathered genocide, famine, wars, and cultural suppression. They tried to silence our language, erase our very identity, yet we endured while they crumbled. Because, as we all know, empires rise and fall, but the steppe remains steadfast, a testament to our resilience.

So, as I sit there, surrounded by the concrete jungle of the city, I find strength in knowing that the steppe will always be with us — a reminder of our enduring connection to the land and to each other.